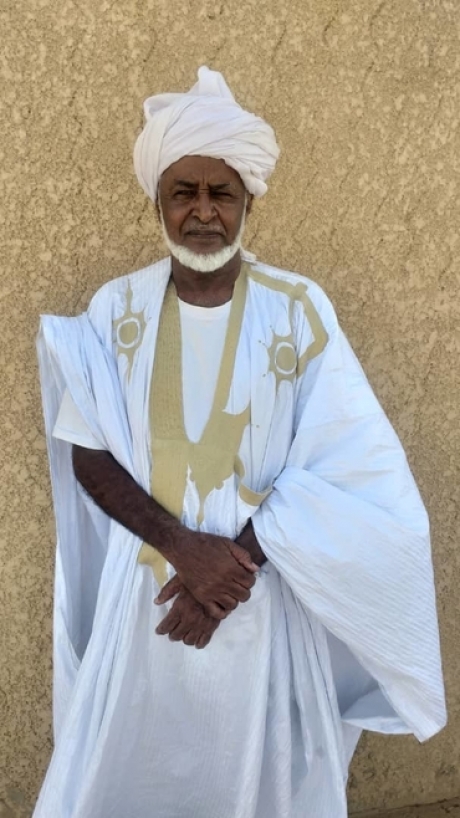

“We have been stranded for almost three months because of the border closure between Mali and Mauritania. We cannot move our livestock, graze our animals or sell them. The animals were hungry, and we had to wait for the rain so that they could finally eat,” Ould Ne Salem says.

A crisis within a crisis

Alongside the COVID-19 restrictions and the drought, Ould Ne Salem highlights yet another problem: a growing conflict between pastoralists who do not own land in either of the two countries. Some, desperate due to the lack of food for their animals, help themselves to farmers’ fields in the region. This causes irreparable tensions with the local population, which eventually becomes problematic for all nomadic pastoralists.

Ould Ne Salem himself is one of the landless nomadic pastoralists, but he refuses to use natural resources belonging to local farmers. He has witnessed the rise of conflicts, which sometimes results in death and injuries, without being able to do anything to help.

“The crisis has worsened because of pastoralists who take straw and wood without permission, destroying the environment in order to obtain resources,” he says.

How can conflict be prevented?

Cross-border movements is often part of the seasonal cycle of pastoralists, providing access to dry- or wet-season grazing resources, or to winter or summer pastures. Due to the nomadic nature of pastoralist activity, herders have specific government-delineated rights to use natural resources in defined corridors of land. They are allowed to cross borders and use land depending on bilateral and international agreements among countries.

One key way of easing conflict in the Sahel countries is to improve land governance. To this end, FAO has supported the creation of multi-stakeholder platforms that bring together people and organisations who have interests in improved land management, including residents, members of local government and organisations that defend the rights of vulnerable groups like pastoralists. The platforms make it possible to establish a dialogue among these actors, who previously never had the opportunity to interact and consult each other, in order to build inclusive land policies that respect everyone’s rights.

In Mauritania, where the land situation is very sensitive, a national platform as well as a local platform has been set up. The Groupement National des Associations Pastorales (GNAP) is a very active member of the national multi-stakeholder platform, advocating for improved governance of tenure for marginalised groups, such as pastoralists.

“These are alarming situations for nomadic pastoralists and for users of natural resources,” says GNAP’s coordinator, Kane Aliou. “The platforms could play an important role in terms of raising awareness and building the capacity of farmers to prepare themselves to manage other crises.”