New bugs, found in Kenya, can help to control major maize pests

Scientists hope that, within the next two to three years, the discovery of these new parasitoids will be an effective way to control these devastating insect pests – which are reportedly behind major maize shortages and billions of dollars worth of damage every year in African countries.

Insect pests, such as maize stemborers and fall armyworm, increasingly challenge food production around the world.

Huge demands for crops have meant agricultural systems have simplified and frequently focused on single crops. When fields are full of a single crop they can easily be found by their insect pests, as opposed to when the crop is mixed in with others. Because of this higher yield losses have more chance to occur.

Climate change – mostly increased temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns – and wild habitat reduction by farmers has added to this by increasing pest pressure and resurgence.

The rapid evolution of pest resistance to chemicals, an increasing organic food market and the negative effects of chemicals on the health of people and the environment, has increased the need to control insect pests biologically.

Biological control uses live organisms to kill or eat the pest insects. These organisms – called natural enemies or antagonists – are predators, parasites or micro-organisms which can bring disease and death.

Insect parasitoids are one form of biological control. These are insects which develop as parasites on other arthropods, mostly insects, causing their death or sterility. They can target each developmental stage of the insect: eggs, larvae or pupae. They’ve received increased attention because they are efficient, cheaper and offer a management strategy that safeguards human health and the environment.

Two species of these parasitoids have been discovered by us and our colleagues in Kenya. They have found to be efficient biological control agents against two major maize pests: the Cotesia typhae to control the maize stemborer, Sesamia nonagrioides, which has invaded France. And Cotesia icipe to control the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in Africa.

Sesamia nonagrioides is an African cereal stemborer that invaded Europe and the near and middle East about 100 000 years ago. It’s become a major pest for maize and, due to global warming, it’s spreading.

The other major maize pest is the fall armyworm. This invasive species, originally from tropical areas in the Americas, invaded sub-Saharan Africa in 2016. It has now spread to Asia and Australia and has the potential to soon spread in Europe. African countries have faced major maize shortages and billions of dollars worth of damage due to the devastation caused by the fall armyworm and the increased cost of pesticide applied.

There are other parasitoids that can kill these pests. But they are not always present in nature. Understanding the prevalence and effectiveness of these other parasitoids is important. We must ensure that the parasitoids that we will introduce won’t interfere with non-target Lepidoptera species and other natural enemies present in nature that can already parasitise the targeted pest.

We hope that, within the next two to three years, the discovery of these new parasitoids will be an effective way to control these devastating insect pests.

COTESIA TYPHAE

The French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD) started conducting studies in Kenya with the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) to evaluate the diversity, abundance and distribution of stemborers and their natural enemies, particularly parasitoids, in wild habitats around cultivated grasses in East Africa.

After about ten years of study, a new species of parasitoid, Cotesia typhae, was discovered. It lays its eggs inside the Sesamia nonagrioides stemborer larvae which are then killed as the parasitoid feeds on them.

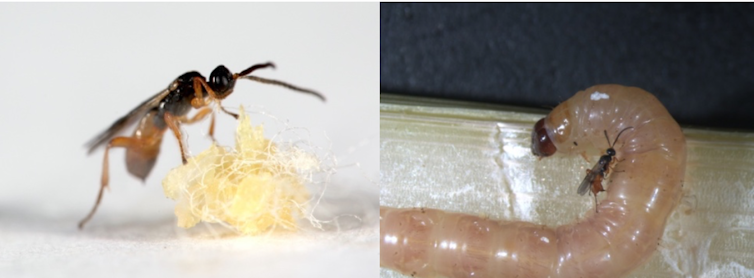

New species of Cotesia typhae (left) parasitising (right) a larva of Sesamia nonagrioides.

Dr. Robert Copeland, Biosystematics Unit, icipe [left] and Laure Kaiser, EGCE, CNRS, France [right]

About 100 000 years ago Sesamia nonagrioides from Africa invaded the Mediterranean zones of Europe and then France. The insect became a major pest as it didn’t come from Africa with any of its natural enemies.

So far, chemical control is the only method that’s been used to reduce infestations in France. But this is a strategy that can negatively affect the health of people and the environment, and so maize growers and professionals are in demand for an efficient biocontrol agent.

After having described this new parasitoid species, the next phase of the study will consist in developing biological control of Sesamia nonagrioides using this parasitoid, Cotesia typhae. We will first need to determine how to ensure it successfully parasitises the French population of the stemborer and to evaluate how introducing this new species might affect non-target stemborers.

COTESIA ICIPE

The second parasitoid, discovered by the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology in Kenya is Cotesia icipe. It was found to be an effective natural enemy of the Fall Armyworm in Africa.

Fall armyworm.

Dr. Subramanian Sevgan, Plant health theme, icipe

The recent “invasion” of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in Africa seriously limit maize yields by infesting the crop throughout its growth stages from, seedling to maturity. The use of chemical pesticides seems to be most common practice used to control the pest, but these can be harmful, particularly to the environment as they can affect non-targeted organisms, like bees.

Through extensive field surveys in East Africa, several indigenous parasitoids which attack the armyworm at its larval stage, were found. This included a new species of parasitoid named Cotesia icipe. It successfully parasitised 45% of Fall Armyworm.

Cotesia icipe.

Dr. Robert Copeland, Biosystematics Unit, icipe

The next phase will focus on developing biological control of the Fall Armyworm in East Africa using Cotesia icipe and other parasitoids.

These studies aim to propose a solution to the lack of full control methods against two major maize pests. It provides good biological control solutions which should fulfil environmental safety regulations while being efficient and economically sound.

We are now putting together feasibility studies for governments, on introducing these parasitoids into their new environments.![]()