Deforestation is driven by global markets

The world is at a crossroads, as humanity tries to mitigate climate change and halt biodiversity loss, while still securing a supply of food for everyone. A recent study in Nature Communications shows that global demands for commodities, especially in connection with agricultural development, are the main drivers of land use change in the global south.

A land use change is defined as a permanent or long-term conversion in the type of cover of an area of land, for instance from forest to urban use, agricultural crops or savanna, or vice versa. The researchers used modern satellite technology, now able to detect changes like deforestation in near real time, to evaluate global trends.

They suggest global land use changes may be happening at a much higher rate than previously thought. The authors found that 17% of the Earth’s land surface has undergone change at least once since 1960, which works out to an area the size of Germany every year. Over that period there was a net forest loss of 0.8 million km², while agricultural crops expanded by 1 million km² and rangelands and pastures by 0.9 million km². No wonder the conversion of forests into agriculture has been flagged by both the Paris Agreement on climate change and its conservation equivalent the Convention on Biological Diversity, as one of the major causes of deforestation.

To halt the destruction of natural habitats, we urgently need to incorporate our “natural capital” – in this case, the environmental benefits of forests and other key ecosystems – into global and national economics. This would be in line with the recommendations of the Dasgupta Review on The Economics of Biodiversity, commissioned by the UK Treasury.

Creating and maintaining woodlands, wetlands and other key ecosystems should become more economically worthwhile than activities like agriculture or mining, or producing fossil fuels, plastics or cement. These activities harm our planet yet still receive US$5 trillion in subsidies and other economic incentives each year, according to the recent United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report Making Peace with Nature.

In practice, this would mean governments subsidising local communities directly to maintain the natural habitats surrounding them, including prevention of wildfires, sustainable use of forest products, managed environmental tourism, to name some examples. This would maintain local communities and encourage them to preserve ecosystems, rather than destroy them to grow crops.

Forest restoration incentives are already bearing fruit in China, and the new study shows the tide of deforestation is being turned in most of the US, Europe and Australia. However the trend in the global south is the opposite, and its evolution over time shows clear connections with global trade and demands for commodities such as beef, sugar cane, soybean, oil palm and cocoa.

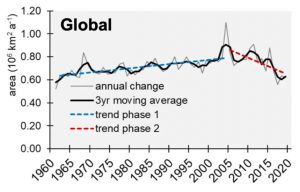

Global rate of land use change increased until 2005 and has since declined. Winkler et al / Nature Communications, CC BY-SA

While the rate of land use change has decreased in the world overall since 2005, the production and export of commodity crops has expanded in the global south in that period. The above graph from the new study shows decreases in land use change occurring during economic recessions like those in 2007-2009 and also the 1970s energy crises.

There are clear links between land use change and global market demands. Over the long term, the general trend has been an increase in economic production mostly associated with environmental destruction. Even moments of environmental awakening such as the major conventions in 1992 could not stop the destruction, as the population continued to grow and consumption increased, shrugging off the constraints of frugality learned in the Great Depression and then reinforced by rationing in the second world war. As the new study shows, in recent decades economic growth in the northern hemisphere has depended in large degree on resource destruction in the developing world.

Much more will be needed to reverse deforestation in the global south, and national subsidies and conservation measures are not enough. We need a system that actually counteracts global markets. We are convinced the solution lies in how each nation calculates its overall income, which nowadays is just done as gross domestic product, or GDP.

The Dasgupta Review set the basis for such national income accounting of natural assets, primarily focusing on ecosystem services – natural pollination, provision of clean air and water, and so on. We would go further and add biodiversity itself – the extension of primeval habitats, or species and genetic richness, for instance. If accounting for such natural assets becomes routine, we believe the global economic system would pay them as much attention as to the more conventional GDP. Such a move would go a long way toward respecting and conserving the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems.

If not, we will keep undermining them and running down the planet’s ability to support the inseparable: intertwined human wellbeing and the rest of life on Earth.