Why agricultural reform is needed to achieve net zero emissions

A quarter of the way into the “super year” for climate and nature – and with eyes firmly fixed on COP26 – policy-makers and activists alike are looking at how to accelerate decarbonisation across the board. They are working towards achieving net zero emissions and the Paris Agreement’s goals of keeping global warming well below 2°C, ideally below 1.5°C.

HOW AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE ARE HEATING THE PLANET

While a transition toward cleaner, less emission-intensive energy systems has been the focus to date, the role of agriculture in generating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – and how to reduce those emissions – is becoming increasingly clear.

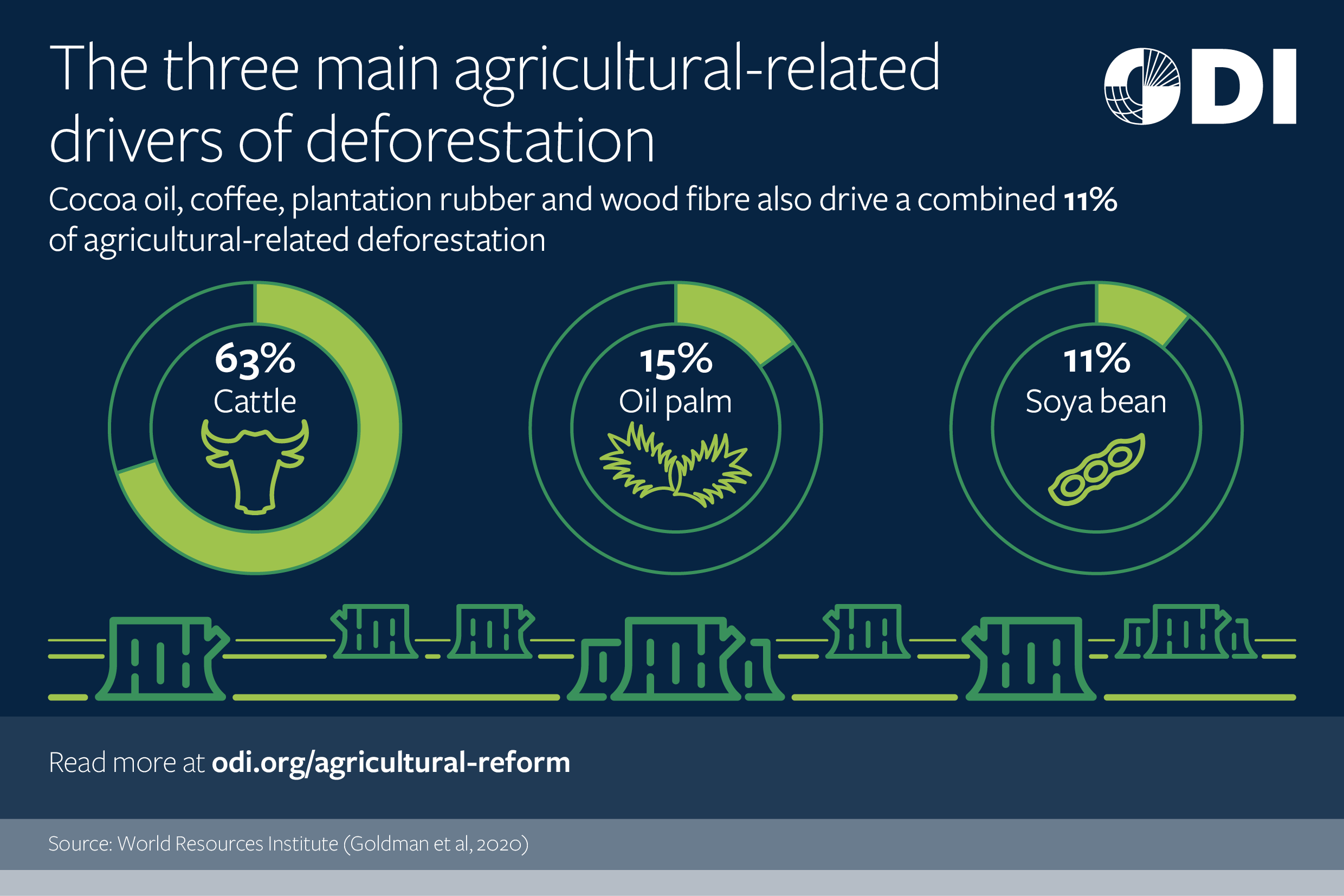

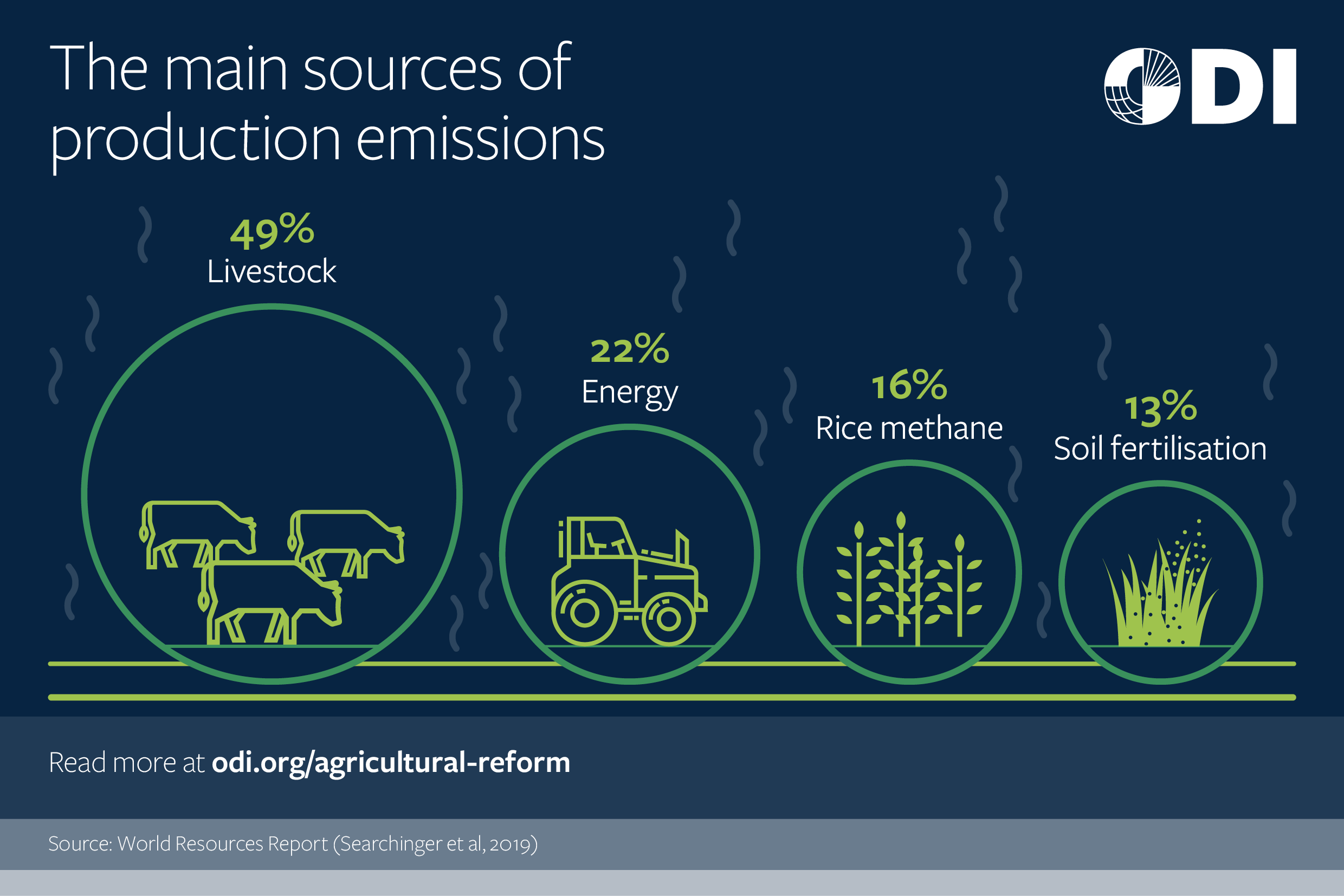

Agriculture is estimated to contribute up to 24% of total GHG emissions worldwide. This is because of the way agricultural goods are produced, as well as the land use change they trigger when forests or peatlands are cleared to cultivate crops or graze cattle.

Agricultural production is also the largest source of methane and nitrogen dioxide emissions. This mainly comes from cattle manure and enteric fermentation, over-application of fertiliser and flooding rice paddies. Agricultural production and land use change can also lead to the conversion of valued habitats or eliminate biodiversity.

DECARBONISING LAND USE

Agricultural emissions can be reduced if we change production practices and minimise land use change. Some ideas include:

- Promoting more accurate fertiliser use and developing improved fertilisers to reduce their emissions footprint.

- Improving management of grazing lands and manure and the productivity of farm animals, as well as reducing enteric emissions through diet modification.

- Cutting the number of ruminants overall by encouraging greater reliance on plant-based diets in key consumer groups in high-income countries (HICs) and emerging economies, where per capita meat consumption is on the rise.

- Reducing the duration of flooding in paddy fields and improving paddy yields.

- Stopping livestock or crop production on forested or peat land.

Alongside reducing farm emissions, another major target is to lock up carbon on land and in the plants that grow on it. For example, agro-forestry – targeted at areas most under environmental pressure and with species appropriate to local ecological systems – has significant potential for carbon capture and storage.

OPPORTUNITIES TO REFORM PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR AGRICULTURE

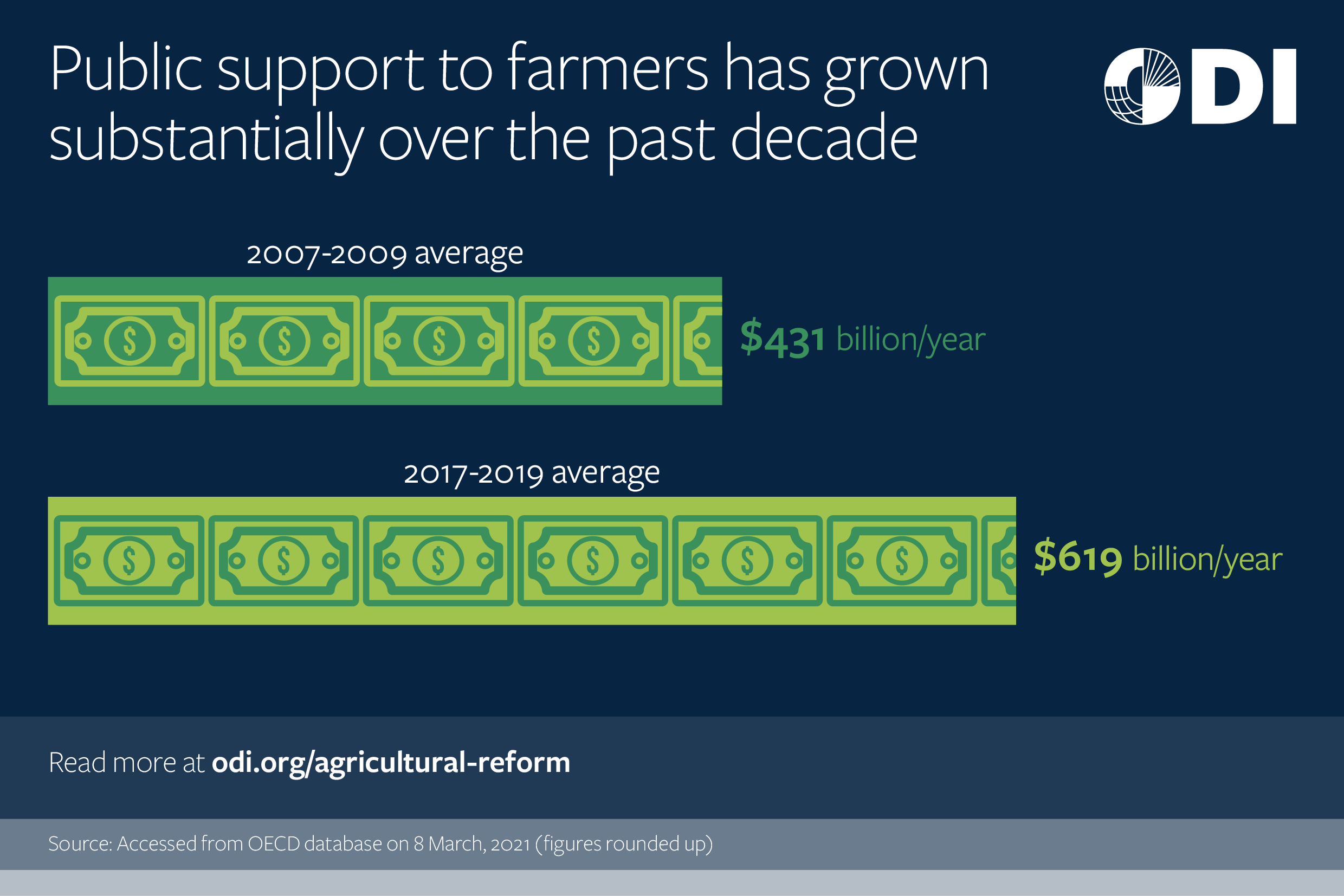

Large amounts of public money are given to the agricultural sector, either directly from government budgets or as a transfer from consumers to producers. This has been growing over the past decade. Globally, agricultural production receives transfers from taxpayers or consumers of up to $619 billion per year. This is almost double the value received by the sector 10 years ago, and 56 times the $11 billion of climate finance aimed at land use.

Public support to farmers can be a major lever for change. It is often introduced for good reasons, mainly to improve food security by increasing aggregate food availability or reducing the cost of food for consumers. Other common goals include protecting farmers’ rural incomes and resilience, stabilising agricultural markets and improving productivity.

But in many cases, the original policy aims have been obscured as public support morphs and recipients’ interests become entrenched. The objectives of the subsidies are not always realised, and much public money can go to large-scale farmers who may need it less than smaller and poorer farmers.

And from a planetary health perspective, the existing structure of agricultural support provides little incentive for farmers to transition from high to low emission-intensive commodities or production practices.

But simply removing payments is not the answer. Initial analysis shows that withdrawing coupled direct payments – which are granted to farmers based on the amount produced – would reduce GHG emissions, but only by 0.6%. Removing market price support in the countries that use this approach could actually increase emissions globally, as global consumption would rise. The production of high emission-intensive commodities would not reduce in countries where market price support is not used.

Public support to farmers needs to be applied differently. Policy-makers should redirect this public money towards environmental public goods, including efforts to stabilise the climate. This includes:

- Reducing emission levels from agricultural production processes and land-use change.

- Establishing incentives for farmers to adjust production levels, output mix and agricultural practices.

- Influencing the composition of diets to reduce meat consumption and enhance overall nutrition.

FIVE WAYS POLICY-MAKERS CAN BETTER SUPPORT THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR

The greatest opportunity lies in redirecting existing support towards payments that are decoupled from output levels. These payments should be applied where they can have the greatest combined social, economic and environmental impact and be conditional on supporting environmental public goods.

1. Move towards decoupled payments

To reduce incentives to expand production, the sector should move away from coupled payments and instead towards decoupled payments, which are not contingent on output.

2. Better target support

Support for the agricultural sector should be targeted more effectively, focusing on regions or sub-regions with the lowest marginal abatement costs, and crops or livestock with the highest GHG emissions intensity. Allowing flexible targeting within national emissions reductions targets – and a mechanism that enables this – will be key.

3. Improve policy coherence

Policy-makers should help to improve policy coherence, making sure that policy instruments are pulling in the same direction. This should ideally reinforce interventions to reduce environmental harm and GHG emissions while achieving other development objectives.

4. Introduce conditionality

Providing public support to farmers should be conditional on achieving environmental goals and producing public environmental goods.

5. Boost research funding

Cutting across all of these measures, policy-makers need to boost funding for research and development. Reducing emissions and other environmental goals must be placed alongside the more traditional research aims of raising productivity and increasing resilience. Public funding also needs to plug the knowledge gaps that still exist to gain a better understanding of what type of support is most climate compatible and how best to achieve policy coherence.

OVERCOMING POLITICAL ECONOMY BARRIERS TO REFORM

Attempts at reforming agricultural policy have often hit political economy barriers. There can be opposition from interest groups benefitting from the status quo, while lack of information about the scale and nature of public support can stall momentum for reform. There are also often concerns about government capacity to manage change and distributional impacts effectively, and existing governance structures can impede deeper reform.

The reforms, policies and investments that are easiest to push through are those that do not arouse any opposition and are a win-win for everyone in terms of trade-offs and cost. Coordinated and creative action both within and across countries can identify policy measures that can meet those criteria, at least as a starting point for reform. These measures can then be translated into a clear reform plan that lays out the phases and their goals, sequenced in a way that frontloads the benefits of reform as much as possible.

But momentum will always need to be generated to move away from the status quo. This can be done by using windows of opportunity such as COP26, COP15 and the Global Stocktake in 2023 to trigger reform. Building and sustaining new coalitions around these opportunities can generate and maintain this momentum.

And finally, a well-constructed communications strategy that delivers clear, well-evidenced messages can make the most of these opportunities. Such messages can correct misconceptions and increase transparency around the nature of public support and the opportunities for making it more climate compatible. They can also be tailored to speak to specific groups, helping to build – and maintain – the coalitions of unusual suspects that are needed to punctuate the equilibrium that can hold back reform.

Global cooperation needs to underpin this to build credibility and trust in the reform process, and exchange learning on how to best achieve the common goals in the Paris Agreement. The “super year” for climate and nature is the ideal opportunity to strengthen such cooperation.